前言 这一系列的课程是Scala专项课程的第二部分,课程名为Functional Program Design in Scala

这里我就把它简写成FPDIS了,和之前记录的笔记一样,这个系列也会记录对应的心得体会以备后续自查

Recap: Functions and Pattern Matching 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 { "firstName" : "John" , "lastName" : "Smith" , "isAlive" : true , "age" : 27 , "address" : { "streetAddress" : "21 2nd Street" , "city" : "New York" , "state" : "NY" , "postalCode" : "10021-3100" } , "phoneNumbers" : [ { "type" : "home" , "number" : "212 555-1234" } , { "type" : "office" , "number" : "646 555-4567" } ] , "children" : [ ] , "spouse" : null }

上面这个JSON(JavaScript Object Notation )在Scala中可以这样表示

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 abstract class JSON case class JSeq (elems: List [JSON ] ) extends JSON case class JObj (bindings: Map [String , JSON ] ) extends JSON case class JNum (num: Double ) extends JSON case class JStr (str: String ) extends JSON case class JBool (b: Boolean ) extends JSON case object JNull extends JSON

假如说我现在有了一段JSON的数据在内存里,如何按照格式把他展开成字符串呢?

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 def show JSON ): String = json match { case JSeq (elems) => elems.map(show).mkString("[" , "," , "]" ) case JObject => val assocs = bindings.map{ case (key, value) => s"" "" ${key}":{show(value)}" "" } assocs.mkString("{" , "," ,"}" ) case JNum => num.toString case JStr => "\"" + str + "\"" case JBool => b.toString case JNull => "null" }

下面一段desugar的代码有助于理解Scala编译器的工作

比如说,当我们看到上面这段构造匿名函数的代码时,其实是什么样子的类型呢?

{case (key, value) => key + ":" + show(value)}

其实这段的类型是(String, JSON) => String

desugar后就是new Function1[(String, JSON) => String]

其中type JBinding = (String, JSON)

其中Function1的签名为

1 2 3 trait Function1 [-A , +R ] def apply A ): R }

这里泛型A/R签名的-/+符号是用来指示对应的型变,这个Martin说会在后续的课程中详细说明(划重点)

这么一来,我们可以把上面的那段代码进行展开

1 2 3 4 5 6 new Function1 [JBinding , String ] { def apply JBinding ): String = x match { case (key, value) => key + ":" + show(value) } }

类似地有

1 2 trait Map [Key , Value ] extends (Key => Value trait Seq [Elem ] extend (Int => Elem

上面地例子由于没有实现对应的JSON类,下面用一个具体的例子来演示

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 val f: String => String = {case "ping" => "pong" }scala> f("ping" ) val res2: String = pongscala> f("abc" ) scala.MatchError : abc (of class java .lang .String ) at $anonfun$f$1 (<console>:1 ) ... 32 elided

对于不存在与定义域内的输入,会抛出异常,但是可以通过PartialFunction来预先确认是否有定义

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 val f: String => String = {case "ping" => "pong" }scala> val f: PartialFunction [String , String ] = {case "ping" => "pong" } val f: PartialFunction [String ,String ] = <function1>scala> f.isDefinedAt("abc" ) val res6: Boolean = false scala> f.isDefinedAt("ping" ) val res7: Boolean = true

PartialFunction对应的函数签名如下

1 2 3 4 trait PartialFunction [-A , +R ] extends Function [-A , +R ] def apply A ): R def isDefinedAt A ): Boolean }

所以,对于上述的代码,会被展开成

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 new PartialFunction [String , String ] { def apply String ): String = { case "ping" => "pong" } def isDefinedAt String ): Boolean = { case "ping" => true case _ => false } }

本小节最后附有练习若干

1 2 3 4 val f: PartialFunction [List [Int ], String ] = { case Nil => "one" case x :: y :: rest => "two" }

对于以上函数,f.isDefinedAt(List(1,2,3))的输出是什么

对于下面的函数

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 val g: PartialFunction [List [Int ], String ] = { case Nil => "one" case x :: rest => rest match { case Nil => "two" } }

g.isDefinedAt(List(1,2,3))的输出是什么

这两个练习可以看出,

PartialFunction只能保证在最外层的match case 中是否存在定义,

不能保证一定有对应的结果

Recap: Collections 对于简单的for-yield语句,直接会翻译成map

如果在for语句中有if条件,那么会加上filter

1 2 for (x <- e1.withFilter(f); s) yield e2

这里是withFilter,它是lazy的,所以不会立刻计算

对于多重循环的情况

1 2 e1.flatMap(x => for (y <- e2; s) yield e3)

可以把for循环和模式匹配(pattern matching)一起使用

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 val data: List [JSON ] = ...for { JObj (bindings) <- data JSeq (phones) <- bindings("phoneNumbers" ) JObj (phone) <- phones JStr (digits) <- phone("number" ) if digits startsWith "212" } yield (bindings("firstName" ), bindings("lastName" ))

上面这段语句提取出json中,会提取出所有的以”212”开头的电话号码的记录的姓和名

对于其中的模式匹配,编译器会这样翻译

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 x <- expr withFilter { case pat => true case _ => false } map { case pat => x }

本小节的练习

1 2 3 4 5 for { x <- 2 to N y <- 2 to x if (x % y == 0 ) } yield (x, y)

这段代码会翻译成什么呢

1 2 (2 to N ).flatMap(x => for (y <- 2 to x if x % y == 0 ) yield (x, y)) = (2 to N ).flatMap(x => (2 to x).withFilter(y => x % y == 0 ).map(y => (x, y)))

Querys with For 这一小节简单讲解了下如何用For来对数据结构进行查询和调优

Translation of For 这一小节基本上是第二小节的重复

Functional Random Gererators 构造随机整数很简单

1 2 3 import java.util.Random val rand = new Random rand.nextInt

如果我们想要用更加通用的方法来生成随机数,该怎么做呢

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 trait Generator [+T ] def generate T } val integers = new Generator [Int ] { val rand = new java.util.Random def generate Int = rand.nextInt } val booleans = new Generator [Boolean ] { def generate Boolean = integers.generate > 0 } val pairs = new Generator [(Int , Int )] { def generate Boolean = (integers.generate, integers.generate) }

这样写的确没什么问题,就是每次都需要写重复的代码,那么可以不可以避免这一点呢

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 trait Generator [+T ] self => def generate T def map S ](f: T => S ): Generator [S ] = new Generator [S ] { def generate } def flatMap S ](f: T => Generator [S ]): Generator [S ] = new Generator [S ] { def generate } }

这里之所以要在外层声明self,是因为,如果不这样做,f(generate)就会被解释成f(this.generate)。在这个函数中this在map里,this.generate就会导致循环调用,为了能够获取到外部的generate,所以事先要声明self type

有了这些准备工作,我们就能直接用for来方便地写代码了

1 2 3 4 5 6 val integers = new Generator [Int ] { val rand = new java.util.Random def generate Int = rand.nextInt } val booleans = for (x <- integers) yield x > 0

这里可以把booleans部分展开

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 val booleans = integers.map{ x => x > 0 }val booleans = new Generator [Boolean ] { def generate Int ) => x > 0 )(integers.generate) } val booleans = new Generator [Boolean ] { def generate 0 }

是不是和最开始的一样了?

如法炮制

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 def pairs T , U ](t: Generator [T ], u: Generator [U ]) = t flatMap { x => u map {y => (x, y)} } def pairs T , U ](t: Generator [T ], u: Generator [U ]) = for { x <- t y <- u } yield (x, y) def pairs T , U ](t: Generator [T ], u: Generator [U ]) = new Generator [(T ,U )] { def generate new Generator [(T , U )] { def generate }).generate } def pairs T , U ](t: Generator [T ], u: Generator [U ]) = new Generator [(T ,U )] { def generate }

有了这些,我们可以方便的写一些辅助函数

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 def single T ](x: T ): Generator [T ] = new Generator [T ] { def generate } def choose Int , hi: Int ): Generator [Int ] = for (x <- integers) yield lo + (x % (hi - lo) + hi - lo) % (hi - lo) def oneOf T ](xs: T *): Generator [T ] = for (idx <- choose(0 , xs.length)) yield xs(idx)

这样我们可以任意生成随机的List

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 def lists Generator [List [Int ]] = for { isEmpty <- booleans list <- if (isEmpty) emptyLists else nonEmptyLists } yield list def emptyLists Nil )def nonEmptyLists for { head <- integers tail <- lists } yield head :: tail

本小节的练习是实现Tree的构造器

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 trait Tree case class Inner (Left : Tree , Right : Tree extends Tree case classs Leaf (x: Int ) extends Tree def leafs Generator [Leaf ] = for { x <- integers } yield Leaf (x) def inners Generator [Inner ] = for { l <- trees r <- trees } yield Inner (l, r) def trees Generator [Tree ] = for { isLeaf <- booleans tree <- if (isLeaf) leafs else inners } yield tree

那么这类生成器到底有什么用处呢?

一个显然的想法就是用这些生成器来构造随机的测试数据

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 package testtoolsimport generator.Generators .{pairs, lists}import generator.Generator object Test def test T ](g: Generator [T ], numTimes: Int = 100 ) (test: T => Boolean ): Unit = { for (i <- 0 until numTimes) { val value = g.generate assert(test(value), s"$i test: test failed for $value " ) } println(s"passed $numTimes tests" ) } def main Array [String ]): Unit = { test(pairs(lists, lists)) { case (xs, ys) => (xs ++ ys).length >= xs.length } } }

Monads

简单的说单子就是自函子范畴上的一个幺半群

前面的省略都是为了能有更多的篇幅来啃Monad

让我们抛开数学范畴论的术语,直接从代码上来讲解

1 2 3 4 5 trait M [T ] def flatMap U ](f: T => M [U ]): M [U ] } def unit T ](x: T ): M [T ]

Monad是包含flatMap操作和unit单位元的数据结构

unit可以让我们把任意元素转换到Monad中

flatMap可以让我们对Monad中的元素进行运算

这样也许过于抽象,下面是一些符合Monad性质的数据结构

List —— unit(x) = List(x)

Set —— unit(x) = Set(x)

Option —— unit(x) = Some(x)

Generator —— unit(x) = single(x)

flatMap是以上所有数据结构都有的方法,它们之间的区别就是unit不同

map也可以由flatMap和Unit来表示

1 2 m map f == m flatMap (x => unit(f(x))) == m flatMap (f andThen unit)

下面我们来介绍更严格的Monad定义

当一个类型(数据结构)满足下面三个条件时,我们将之称为Monad

结合律

1 m flatMap f flatMap g == m flatMap (x => f(x) flatMap g)

存在左单位元

1 unit(x) flatMap f == f(x)

存在右单位元

下面用例子来具体说明上面的性质

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 // 这里由于和自带的关键字同名,所以无法编译,意会就行 abstract class Option[+T] { def flatMap[U](f: T => Option[U]): Option[U] = this match { case Some(x) => f(x) case None => None } }

下面简单证明下符合以上三条性质

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 1. ∵ Some (x) flatMap f == f(x) ∴ 存在左单位元 2. ∵ opt flatMap Some == opt match { case Some (x) => Some (x) case None => None } 无论opt为Some (x)还是None 结果都为 opt flatMap Some == opt ∴ 存在右单位元 3. 对于式子 m flatMap f flatMap g == m flatMap (x => f(x) flatMap g) 左边 = opt flatMap f flatMap g == opt match { case Some (x) => f(x) case None => None } match { case Some (x) => g(x) case None => None } == opt match { case Some (x) => g(f(x)) case None => None } 右边 = opt flatMap (x => f(x) flatMap g) == opt match { case Some (x) => f(x) flatMap g case None => None } 而 f(x) flatMap g == g(f(x)) ∴左边=右边 结合律满足

看完上面这一通证明,你也许会好奇,这到底有什么用?

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 for { y <- for (x <- m y<- f(x)) yield y z <- g(y) } yield z == for { x <- m y <- f(x) z <- g(y) } for (x <- m) yield x == m

接下来再介绍一个“Monad”类型Try,函数签名如下

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 abstract class Try [+T ] def flatMap U ](f: T => Try [U ]): Try [U ] = this match { case Success (x) => try f(x) catch {case ex: Exception => Failure (ex)} case fail: Failure => fail } def map U ](f: T => U ): Try [U ] = this match { case Success (x) => Try (f(x)) case fail: Failure => fail } } case class Success [T ](x: T ) extends Try [T ]case class Failure (ex: Exception ) extends Try [Nothing ]object Try def apply T ](expr: => T ): Try [T ] = { try Success (expr) catch { case ex: Exception => Failure (ex) } } }

这里用了call by name的传入参数方式,这样不会立刻计算expr

对于下面的使用

1 2 3 4 for { x <- computeX y <- computeY } yield f(x, y)

如果computeX和computeY都成功调用,那么返回的结果是Success(x)和Success(y)

如果任意一个调用失败,都会返回Failture(ex)

事实上,如果按照那三条规则检验,就会发现

Try(expr) flatMap f != f(expr)

左边不会抛出异常,而右边会

但是这个能和For很好的配合

有的时候,不需要完全符合三条性质也能使用,更深的理解就配合使用来加深印象吧

作业QuickCheck 作业的代码下载地址为:http://alaska.epfl.ch/~dockermoocs/handouts-coursera-2.13/quickcheck.zip

下面是一个纯函数式(不对数据进行修改)的堆的实现

具体的论文地址为:http://www.brics.dk/RS/96/37/BRICS-RS-96-37.pdf

二项式队列 二项式队列是由树组成的

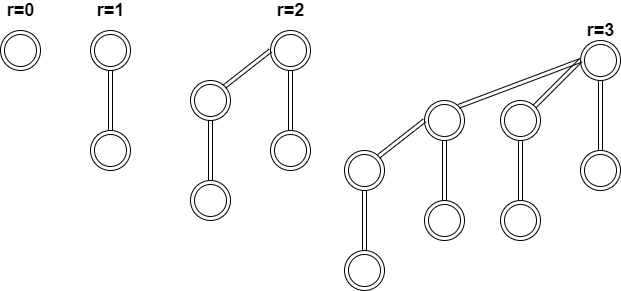

binomial tree递归定义如下

rank 为 0 的binomial tree是单节点

rank 为 r+1 的binomial tree是由两个 rank 为 r 的binomial tree连接组成,假如我们把这两个rank为r的binomial tree称为a,b。其中连接方式为,a的根节点连接到b的根节点的最左边的子节点的位置

一图胜万言

从这个定义里,可以显然发现,rank r的binomial tree有2^r个节点

除了上面的递归定义外,还有一个更方便的定义来描述binomial tree

rank r 的树有r个子节点 t1 t2 … tr , 其中ti 是一个rank (r-i) 的binomial tree

一个binomial tree,如果对于它的所有节点,都满足父节点小于等于其子节点,那么我们说这个binomial tree是已经堆有序 (heap-ordered)的

为了在连接两个binomial tree时维护堆有序的状态,我们将根较大的树设为根较小的树的子树。

一个二项式队列是一个由堆有序的binomial tree组成的森林,这个森林中,任意两个binomial tree都有着不同的rank

举个例子,一个大小为21的二项式队列,21的二进制表示为10101,所以这个二项式队列是由rank 0, rank 2, rank4 的binomial tree组成的

我们现在已经做好了描述二项式队列各项操作的准备。因为在二项式队列中,所有的树都已经是堆有序的了

对于一个有n个节点的二项式队列,最多包含

我们知道,二项式队列中的最小元素就是某一个树的根节点,这样我们只要对所有的树依次扫描,花费O(log n)的时间复杂度,就能找到最小的元素

当我们需要往二项式队列里插入节点时,我们首先创建一个只有一个节点的树,接下来我们就按照rank增加的顺序,依次遍历所有的树。

在遍历的过程中,连接具有相同rank的树,直到我们找到了一个”空闲”的rank位置为止,相当于在对二进制数做进位运算。假如我们对一个大小为21的二项式队列插入一个节点,那么森林的组成会由原来的rank0, rank2, rank4,变成 rank1, rank2, rank4。这样做的话,最坏的情况是将节点插入到rank最大的树上,

在这种情况下,需要遍历k个树,同时连接k个树,对应的时间复杂度是 O(log n)

类似地,二进制加法就对应着两个二项式队列的合并,同理可得,所需要的时间复杂度也是 O(log n)

在这里面,最棘手的操作是删除二项式队列中最小的节点

我们首先在队列中删除根节点最小的树,但是却需要保留它的子节点,子节点本身需要做合并的操作。

以上操作需要的时间复杂度为O(log n)

对应的实现代码如下

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 trait Heap type H type A def ord Ordering [A ] def empty H def isEmpty H ): Boolean def insert A , h: H ): H def meld H , h2: H ): H def findMin H ): A def deleteMin H ): H } trait BinomialHeap extends Heap type Rank Int case class Node (x: A , r: Rank , c: List [Node ] ) override type H List [Node ] protected def root Node ) = t.x protected def rank Node ) = t.r protected def link Node , t2: Node ): Node = if (ord.lteq(t1.x, t2.x)) Node (t1.x, t1.r + 1 , t2 :: t1.c) else Node (t2.x, t2.r + 1 , t1 :: t2.c) protected def ins Node , ts: H ): H = ts match { case Nil => List (t) case tp :: ts => if (t.r < tp.r) t :: tp :: ts else ins(link(t, tp), ts) } override def empty Nil override def isEmpty H ) = ts.isEmpty override def insert A , ts: H ) = ins(Node (x, 0 , Nil ), ts) override def meld H , ts2: H ) = (ts1, ts2) match { case (Nil , ts) => ts case (ts, Nil ) => ts case (t1 :: ts1, t2 :: ts2) => if (t1.r < t2.r) t1 :: meld(ts1, t2 :: ts2) else if (t2.r < t1.r) t2 :: meld(t1 :: ts1, ts2) else ins(link(t1, t2), meld(ts1, ts2)) } override def findMin H ) = ts match { case Nil => throw new NoSuchElementException ("min of empty heap" ) case t :: Nil => root(t) case t :: ts => val x = findMin(ts) if (ord.lteq(root(t), x)) root(t) else x } override def deleteMin H ) = ts match { case Nil => throw new NoSuchElementException ("delete min of empty heap" ) case t :: ts => def getMin Node , ts: H ): (Node , H ) = ts match { case Nil => (t, Nil ) case tp :: tsp => val (tq, tsq) = getMin(tp, tsp) if (ord.lteq(root(t), root(tq))) (t, ts) else (tq, t :: tsq) } val (Node (_, _, c), tsq) = getMin(t, ts) meld(c.reverse, tsq) } }

回到正题 这里还会用到ScalaCheck

在代码中,有多个实现,只有一个是正确的,其他的都有Bug,你需要编写测试来测试出Bug。

这个作业非常贴心地给出了例子,教你如何写生成器

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 lazy val genMap: Gen [Map [Int ,Int ]] = oneOf( const(Map .empty[Int ,Int ]), for { k <- arbitrary[Int ] v <- arbitrary[Int ] m <- oneOf(const(Map .empty[Int ,Int ]), genMap) } yield m.updated(k, v) )

arbitrary[T] 是一个产生 T 类型数据的生成器,这里我们需要生成的是 Int 类型的 堆

oneOf(gen1, gen2) 是一个随机的选择函数

const(v) 是用来构造一个总是返回 v 的生成器

那么仿照着来写下

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 package quickcheckimport org.scalacheck._import Arbitrary ._import Gen ._import Prop ._abstract class QuickCheckHeap extends Properties ("Heap " ) with IntHeap lazy val genHeap: Gen [H ] = for { x <- arbitrary[Int ] h <- oneOf(genHeap, const(empty)) } yield insert(x, h) implicit lazy val arbHeap: Arbitrary [H ] = Arbitrary (genHeap) property("findMin" ) = forAll { (h: H ) => val m = if (isEmpty(h)) 0 else findMin(h) findMin(insert(m, h)) == m } }

这样编写的基础测试的通过率为 4/7

我们来看下这个测试的反向check

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 def asProp Properties ): Prop = Prop .all(properties.properties.map(_._2).toSeq:_*) def checkBogus Properties ): Unit = { def fail throw new AssertionError ( s"A bogus heap should NOT satisfy all properties. Try to find the bug!" ) check(asProp(p))(identity) match { case r: Result => r.status match { case _: Failed => () case p: PropException => p.e match { case e: NoSuchElementException => () case _ => fail } case _ => fail } } } @Test def `Bogus 1 ) binomial heap does not satisfy properties. (10 pts)`: Unit = checkBogus(new QuickCheckHeap with quickcheck.test.Bogus1BinomialHeap ) trait Bogus1BinomialHeap extends BinomialHeap override def findMin H ) = ts match { case Nil => throw new NoSuchElementException ("min of empty heap" ) case t :: ts => root(t) } }

以上面这段为例

Bug的引入在于错误地实现了findMin函数

检查错误时,我们希望对于编写的测试,对有Bug的实现能找到反例,所以定义了一个辅助函数checkBogus

这个函数的行为和一般的测试相反,当匹配到反例或者NoSuchElementException时认为正确,其他情况认为是错误。

我们只要编写新的property来卡掉不正确的实现就行了

这里就要详细查看论文和对应数据结构的实现了,才能对症下药

我们可以看到,错误的实现改写的部分

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 trait Bogus1BinomialHeap extends BinomialHeap override def findMin H ) = ts match { case Nil => throw new NoSuchElementException ("min of empty heap" ) case t :: ts => root(t) } } trait Bogus2BinomialHeap extends BinomialHeap override protected def link Node , t2: Node ): Node = if (!ord.lteq(t1.x, t2.x)) Node (t1.x, t1.r + 1 , t2 :: t1.c) else Node (t2.x, t2.r + 1 , t1 :: t2.c) } trait Bogus3BinomialHeap extends BinomialHeap override protected def link Node , t2: Node ): Node = if (ord.lteq(t1.x, t2.x)) Node (t1.x, t1.r + 1 , t1 :: t1.c) else Node (t2.x, t2.r + 1 , t2 :: t2.c) } trait Bogus4BinomialHeap extends BinomialHeap override def deleteMin H ) = ts match { case Nil => throw new NoSuchElementException ("delete min of empty heap" ) case t :: ts => meld(t.c.reverse, ts) } } trait Bogus5BinomialHeap extends BinomialHeap override def meld H , ts2: H ) = ts1 match { case Nil => ts2 case t1 :: ts1 => List (Node (t1.x, t1.r, ts1 ++ ts2)) } }

编写测试有两种思路,一个是想出尽可能多且完备的测试来覆盖所有可能的情况

另一种就是针对性地构造hack测试,用尽可能少的测试分别暴露出每一个的问题

对于Bogus1BinomialHeap

1 2 3 4 5 6 trait Bogus1BinomialHeap extends BinomialHeap override def findMin H ) = ts match { case Nil => throw new NoSuchElementException ("min of empty heap" ) case t :: ts => root(t) } }

和正确的实现相比,他没有去ts部分寻找最小值

比如这个值,就会错

1 List(Node(0,0,List()), Node(-1,1,List(Node(-1,0,List()))))

我们写下的随机数据,插入一个最小值再返回就会出错

1 2 3 4 property("findMin" ) = forAll { (h: H ) => val m = if (isEmpty(h)) 0 else findMin(h) findMin(insert(m, h)) == m }

同样的方法可以构造一些其他的测试,这里就不再赘述了。